In the Next Issue

The next issue will be devoted to reproduction – and we want your views. We already have some of the copy lined up – but we need more papers, reports of conferences, workshops, articles, etc. In the report on the Northern region you will find more about this – recent developments in the region around this issue has given us the impetus to plan this special issue (which obviously won’t be the last to discuss reproduction!) Please try and send things for publication by Christmas.

SCARLET WOMEN – an internal paper or open circulation?

We have had several requests from left bookshops (not specifically feminist), from libraries, research organisations (‘left’), universities etc. for Scarlet Women. We don’t think we as a collective have the right to make Scarlet Women available for general circulation without asking both contributors and readers what they think. There is a point-of-view which says our views should reach the widest circulation possible. The opposing view says that what we write is subversive, and that our present internal disagreements should be kept to ourselves. We won’t make a decision about this until the National SOCFEM conference in January, and we want groups and regions to come prepared with some sort of view already thrashed out, so that there can be a constructive discussion and hopefully a decision at the conference.

Subscriptions

At last we’ve got it together to have Scarlet Women printed – at the fifth attempt! (There’s still a lot of typing though). This means that costs have risen slightly and the charge of 20p per issue doesn’t quite cover costs. We are therefore putting the price for NEW subscribers up to £1 for 3 issues instead of £1 for 5. Present subscribers of course will get SW at the old price until their sub. runs out. If your subscription runs out with this issue there will be a tick in the box below.

Editors Introduction to SW5

The main theme of this issue revolves around questions of theory and, specifically the differences in theory between those sisters who call themselves revolutionary feminists and those, like us, who call themselves socialist feminists. We are reprinting here several papers from the Revolutionary Feminists’ Conference held in Edinburgh last summer because we feel that many of the questions they raise are of great importance to us as well.

There are also two papers by socialist feminists. The first, by a group of women in South London, it is a critique of Sheila Jeffreys’ papers, two of which are reprinted here. A third paper by her, ‘Worker Control of Reproduction’ can be obtained from Catcall* – we didn’t include it because it is quite long and seems to have had quite a wide circulation already. The second socialist feminist paper ‘some notes on sex and class’ is an outline of theoretical position which differs in important respects from both the usual marxist analysis of women and revolutionary feminist analysis.

We hope the papers will stimulate discussion and development of the ideas contained in them. As Sheila Jeffreys argues in her paper ‘the need for Feminist Theory’, we lack theory and thus also strategy in the WLM and both are vitally necessary if we are to achieve our objective. So, we look forward to receiving lots of comments from both groups and individuals and hope to be able to continue the discussion on theory in future issues of Scarlet Women through your contributions.

Papers from the Feminism and Ireland Workshop June 1977

These papers form a collection of essential background reading for an understanding of the position of women in Ireland today. They cover, in brief: the history of British Imperialism in Ireland, the Republican struggles in the South and the effect of partition in the North, the influence of the Catholic Church and its effects on women, the position of women today in both the SOUth and North, and account of the origins and development of Derry Women’s Group, and several other contributions, including one by Big Flame on the way in which women’s involvement in the current struggles in Northern Ireland is forcing changes on their traditional role in relation to men.

Taken as a whole they provide a basis upon which we in England can develop a strategy for action in solidarity with our Irish sisters and in aiding their struggle, aid our own in this country.

PAPERS FROM REVOLUTIONARY FEMINISTS

Feminism and Socialism – Finella McKenzie

(Note: We wrote to Finella at the only address we had for her, asking permission to print her paper. As she hasn’t replied, we assume she’s moved, and hope that since the paper was printed for the Edinburgh conference in July, she welcomes it’s wider circulation!)

There has always been some sort of minority tradition in the left which questioned the position of women. This has been linked through the ages with people such as Mary Wollstonecraft, William Thompson, Robert Owen, Saint Simon and Fourier, and with ideas ranging from the need for a female Messiah to Fourier’s belief that the position of women was an important indicator of the level of civilisation achieved by different societies. But though Fourier’s ideas were relatively some of the most developed of the early socialists (over economics and women’s oppression) they remained at a Utopian level – he believed that somehow, by mere goodwill, the existing social inequalities would cease and thus an egalitarian society would evolve.

Marx was to use Fourier’s ideas about Women’s Liberation in his earlier writings – accepting the concept of the position of women as being an index of general social advance. But in doing so he transformed them by making their application more diffuse – hence women’s position was not solely an index of general social advance, but am index in the more basic sense of the progress of the human over the animal, the cultural over the natural. So it became something of universal importance at the cost of obscuring its substance in relation to women.

This same generalised approach to women appears in his later writings. In his analysis of the family, women as such, their position within the family (in any other than a totally economic sense), are totally ignored. He saw the family as part of the productive forces, and made the connection between the worker’s sale of labour power as a commodity and the women’s sale of her body (in family and out – “Prostitution is only a specific expression of the universal prostitution of the worker”), and said that once women had become part of the labour force, as she became increasingly independent financially her body would no longer be the property of men, and she would be on the same footing as workers in public industry. However it has not been shown to be so as more and more women are becoming workers. He sought to establish this view historically through studying pre-capitalist societies – and came to the conclusion that the family was the result of the “first incipient loosing of the tribal bonds” (some sort of primitive communism).

Engels developed these ideas in The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State after Marx’s death. He sees the inequality of the sexes as probably the first antagonism within the human species. It is an economist account, based around inheritance. Originally inheritance was matrilineal (through the female line), but with increasing wealth and the appearance of private ownership of property it became patrilineal. The wife’s fidelity became essential – to produce children of undisputed paternity – and monogamy was established. Thus she became a private servant, as opposed to a public one in the communistic patriarchal family – and the subordination of women results. Men had appropriated women as private property. So the first class oppression is that of women by men. The primary cause is her physiological weakness. He ends by reducing the problem of women to her capacity to work. So in conclusion the ability to work would liberate her by making private domestic labour public (reintroduction of the female sex into public industry) and mean that the family as an economic unit in society would be abolished.

However, contrary to these views, the absorption of women into the labour force has merely resulted in women having work both inside and outside the home. And rather than abolishing the family as an economic unit, the consequent reduction in family size has made the continuation of the individual nucleus of the family possible. Further, we should be wary of the analogy of female oppression with class exploitation. The notion of women as a class, the Proletarians in marriage, means that only the economic aspects of women’s oppression are discussed. The sexual difference between men and women is obscured, as are the sexual relations which are part of (because reflected in) a whole human relationship to the society they are present in.

Nor can we really think of sexes as class, for individuals are able to move from one to another, but women cannot because men. The victory of the proletariat means the abolition of classes, but the victory of women doesn’t mean the abolition of sexes via the abolition of men. It is a confusing analogy. The family too seems to have a more complicated connection to production and ownership of property. It does not necessarily change neatly or predictably as these are transformed.

Further, the anthropological material he used to base his analysis on came from one source only – Morgan, part of the evolutionary school, which is concerned with tracing back the origins of human society. They regard the development of human society as a kind of childhood in which children grew up in the same way. Certain characteristics are present at certain defined stages of society only (i.e. private property in capitalism). They talk about a prehistoric period – using existing primitive societies and myths. But you cannot with any certainty recreate the earliest societies from abstractions about existing ones – it has to remain a hypothesis. And it is by no means certain what functions myths have -whether they are descriptions of specific historical happenings, or a means to understand a reality that remains hidden, or as a means to bolster the claims of one group against another. So myths about an age in which women were not subordinate (Engels’ universal primitive communism) in no way prove that such societies existed. There is even disagreement among anthropologists about whether there ever was a universal stage of communal ownership that preceded that of private ownership. And finally there is not necessarily a connection between a system of inheritance (i.e. Engels’ matrilineal account) and the political, social, economic dominance of women.

Unfortunately, until recently, since the evolutionist method was attacked by later anthropologists, they’ve neglected to ask the kinds of questions Engels felt were important about ownership and women’s position in society. And since the 1920’s too many Marxists have neglected the role of the family in historical development and have contented themselves with a return to Engel’s system. But Marx and Engels on the position of women suffer the same charge as the earlier socialists on economics. They don’t really understand how the social injustice of sexism has evolved, maintained itself, or how it could be eliminated. They only recognise sexual class where it overlaps their economic analysis. They are unable to evaluate it in its own right. And neither was able to show how socialism would change women’s condition. Given that they were obviously trapped in the cultural bias of their time, it seems dangerous to try and squeeze feminism into an orthodox Marxist framework, and accept their narrow interpretations of sex-class as dogma.

Bebel provided a slight advance on this analysis incorporating the maternal function as one of the fundamental conditions that made women economically dependent on men. But even he believed that sexual equality was impossible without achieving socialism first.

So overall there is no revolutionary theory that accords a direct place to women’s oppression and liberation. It’s been traditionally held among reformist groups who are happy with the existing system of capitalism and want legal and economic equality within it, and among socialist groups, that women can achieve equal rights under capitalism. In the case of the socialists, this leads on to the idea that, since no-one can hope for more than this idea of equality until after the achievement of socialism, the political demands that women make can be accommodated within the prevailing system, and hence are reformist and therefore secondary to the primary revolution. This is a reflection of how women’s issues are seen within capitalist society itself. It is a serious error for the left to regard tokenism as evidence of the weakness of demands and not of the strength of the system.

Reforms can have an important role in revolutionary politics so long as the demand for them is made in the context of their wider implications – with a consciousness beyond the single issue reform, as part of the whole revolutionary struggle for feminism and socialism.

The extent of the absence of women in socialist theory and practice is enormous. Where analysis has been offered it’s been on the whole inadequate, for the resulting practice has seriously failed to match it.

Many women however continue to work within the existing leftist analysis Some (feminist politicos) realise the inadequacy of past socialist theory of women’s position, believing that he theory is not limited in itself and such an analysis (where women’s issues are central to a larger revolutionary struggle for changing the mode of production from feminist to socialist) can be provided and incorporated; others feel their primary loyalty to the left rather than to WL. They regard WL as an important wing of the left to radicalise as yet apolitical women into the larger struggle. Feminism is only a side issue to “real” radical politics (male created) and mist fit into it, instead of being seen as central and radical in itself; and yet others are much more middle of the road. They see the enemy as the system solely, and shift the burden of responsibility to the institutions. Many groups also form women’s caucuses to agitate against male chauvinism within the organisation. These are reformist in the worst sense in that they are trying to improve their position within the limited area of leftist politics.

The feminist politicos while recognising that women must organise around their own oppression, try to fit these activities into the existing leftist analysis and framework of priorities – in which women never come first. Both the other groups won’t even go this far. They ignore the need to organise around their own oppression the need for the end of power relations and leadership; and the need for a mass base of feminist women. It seems that all the most important principles of radical politics just don’t apply to women.

They will never be able to evolve a comprehensive politics, because they have not confronted their oppression as women – hence their inability to put their own needs first; and their need for male political approval (although anti-establishment approval) by accepting that their issues are secondary to the primary struggle. It is sadly very easy for radical women to accept their own exploitation in the name of some larger justice which excludes half the world because as women we are conditioned from childhood to consider ourselves second.

Perhaps the most blinkered view is that which blames the system and its institutions – without realising that men created the system and that the institutions are their tools to preserve it. It implies that men and women are equally oppressed – denying the fact that men benefit from the oppression of women in many ways. And worst, it gives men the excuse that they cannot do anything about it.

This evasive attitude of the male left is prevalent in many spheres, e.g. their condescending attitudes when talking about their women’s caucuses. They really only see WL as something for their girlfriends to do with other women. They cannot conceive that they too should be taking responsibility, dealing with their own oppression and actively combating the sexism in male caucuses; meeting for just that purpose. In the final analysis it just isn’t that important to them – their fellow man, so long as he is a worker, is far more important than their fellow woman. For socialist women t accept such an attitude is complete indulgence. It is all very well to realise that men are oppressed by sex-roles and have been damaged by the society that damaged us. But we should be violently angry that these men are not prepared to do anything about it, and have created within the movement a microcosm of that oppression in society and are proud of it.

WL groups attempting to work within the pre-existent leftist movement haven’t a chance. All they do – their analysis, tactics, values, etc., are shaped and dictated from above by men – whose male supremacist power they are protesting against as WL. If such a male dominated socialist revolution were to occur tomorrow, it would be no revolution, only a coup d’etat amongst men.

Sexism is all-pervasive. Every part of our lives is affected by it – we are exploited as sex-objects, breeders, domestic servants and cheap labour. Oppressed women are found in all exploited minorities; in all social classes, in all radical movements, and at the bottom of the scale of workers. So radical feminism is the first movement that has the potential of cutting across all class, race, age, and geographical barriers since in all these groups women play fundamentally the same role.

But despite being the most international of any political group, the oppression of women is experienced in the most minute and isolated area – the home. Women come into the movement full of unspecified frustration and find what they thought was an individual problem is a political problem. But because as women we have so long had a separate world of our own in the home, and because we’ve lived so intimately with our ‘oppressors’, our oppression is hidden from consciousness and appears to be ‘natural’.

To overcome this acceptance of the situation, radical feminism uses the ‘politics of experience’ in ‘consciousness-raising’ i.e an analysis of society from the perspective of oneself. (R.D.Laing: “no-one can begin to think, feel or act now except from the starting-point of his or her own alienation”) – thus fusing the personal with the political.

This process used in “consciousness raising” can be truly revolutionary. Politics has to be linear – move from the individual to the small (consciousness raising) group to the whole society. It is a tool to develop a politics, not an end to itself. To be a genuine ally of others we have to have fully comprehend our oppression via this method.

So the theory of radical feminism comes out of human feeling, not textbook rhetoric. It unites women at the level of their oppression as women – not on a specific level such as class, race, etc., – and so sets itself the task of analysing such divisions that keep us apart as women, and works to close them. It believes that the lack of an understanding of women’s oppression on the left is due to limitations within the leftist theory itself, not just that such analysis is underdeveloped in that sphere. It sees sex-class as fundamental – for unlike economic class it sprang from biological reality. It says that the first division of labour was that between men and women due to women’s reproductive capacities (and no technology to control them at all) and man’s greater physical strength. Women throughout history, before birth control, were at the mercy of their biology – menstruation, menopause, constant childbirth, wet nursing of infants etc, which made them dependant on men, whether father, brother, husband, lover or whatever – depending on the society – be it matriarchy or patriarchy, for physical survival during these times which were constantly recurring. This set up an inherently unequal power distribution within the biological family. This is true of every society, no matter how many tribes anthropology can dig up where the connection of the father to fertility is unknown, no matter how many matrilineages, cases of sex-role reversals or matriarchies. Likewise this is present in every variation on the biological family – such as today’s relatively recent patriarchal nuclear family.

But to say it is biological and natural in now way harms our case. We are no longer animals, we have a technology developed (though not easily available) that can control such biological inconveniences. Human society does not passively submit to nature, but takes over control of it for its own behalf. As Marx said, the ‘natural’ is not necessarily the ‘human’ value.

However the new technology is often used against us to reinforce our exploitation, so technology alone won’t give us freedom. We have to go further and question the way we all relate to each other – women to women, men to men, women to men and within ourselves; to oust the psychology of power relationships which has by now become an integral part of our psychic make up after thousands of years of playing the roles of dominance/submission.

The problem therefore isn’t simply reducible to one agent of our oppression. It is both our biology, lack of technology to control it (until recently), and men who turned the dependency elicited by our biology into the psychological dependency which was reinforced so totally, over such a long period of time, that we came to believe that we were inferior and our treatment justified. Now with the technology to control the natural, the only obstacle is that which men have psychologically induced into us, into them, in culture and society. Because they are not the sole agent in bringing us to the position we are now in doesn’t mean that they can escape blame. We won’t accept their solely economic analyses which ignore their responsibility in our oppression as women. All men dominate and have oppressed women, by virtue of being men within this society; a few men dominate other groups be it economically, racially, imperialistically or whatever.

However to say that the division of the sexes was the first oppression that underlies all oppression, and is universal – although no doubt true – is too general and nonspecific a truth. It is important that we don’t stop here and accept this as a complete analysis and theory – that we examine exactly how all aspects of our oppression function in order to overcome them within any specific society.

And further we must not fall into the same trap as the economists and ignore all but our own oppression. To understand one’s own oppression doesn’t necessarily mean an automatic comprehension of ways in which other groups are exploited and oppressed. We need to have a wider understanding, a complete and total approach, to have a fully developed political consciousness – which can only comes from knowledge and understanding of the relationships of all classes and divisions in society.

Our analysis and politics of our oppression is still at an early stage of development. In time we shall have one as comprehensive as the Marxists one was for economics. We have not thrown out the insights of the socialists on economics, and we do believe that whereas the oppression of women is intrinsic to capitalism it isn’t to socialism. But for the economic revolution to be a true revolution, it must be accompanied by a sexual revolution. Nothing can justify the attitudes of the economist expressed in ‘wait until after the revolution’. We must overthrow at one blow all oppressive situations – sexual, economic, racial, etc., – beginning right now in each of our personal lives.

I believe radical feminism, by its nature, of cutting across all class, race etc., divisions, has room in it to embrace other analyses of oppression from these groups, and as such is probably the only revolutionary group that will be able to establish a fully egalitarian society.

Bibliography

- The Dialectic of Sex – Shulamith Firestone

- Women’s Estate – Juliet Mitchell

- Origins of the Family, Private Property and the State – Engels

- Hidden from History – Sheila Rowbotham

- Man’s Rise to Civilisation – Peter Farb

- Sisterhood is powerful (anthology of writings from WL)

FEMINISM WHEN IT TRULY ACHIEVES ITS GOALS, WILL CRACK THROUGH THE MOST BASIC STRUCTURES IN OUR SOCIETY – Shulamith Firestone

Sex Class – Why is it important to call women a class? By Jalna Hanmer, Cathy Lunn, Sheila Jeffreys and Sandra McNeill

We need a word which will allow us to:

- Develop an analysis

- Identify ruling class interests and methods of control

- Develop consciousness of shared exploitation among women and their revolutionary anger

Class seems the most suitable word because:

- It has dynamic connotations, unlike group, sex or caste – by dynamic we mean revolutionary force connotations.

- It implies the existence of another class which sets up the institutions and social power processes that control, dominate and exploit women.

- It makes women realise their potential power

- It implies confrontation. Thus differentiating revolutionary/radical feminism from all others. It does not imply liberal reformist solutions.

- It indicates that women’s oppression is not accidental, that it stems from a complex highly organised system of patriarchy.

We recognise the disadvantages of using the word (arising primarily because it suggests a Marxist analysis). For example,

- It could suggest the oppression of women was based solely on economic factors and on our analysis women’s oppression has a wider and more fundamental material basis. The material basis of our oppression comes from the biological fact that there are two sexes and all the other material and psychological aspects developed thereafter.

- It could suggest that class might disappear in the ‘classless’ society of the future, and class according to our analysis will not disappear since it is not just about power but power based on biological differences

- As a purely descriptive word it has been exploited by male theorists and they say we cannot make it mean what we want it to mean. As this may be said of the language as such it hardly seems a decisive objection.

Thus we choose to say that women are a class in our analysis of women’s oppression and to outline the manner in which all mean derive benefits from the oppression of all women. It is necessary to distinguish between the gains which can go to individual men and the gains which go to the Patriarchy as a whole, at the expense of women. Individual men may refuse some benefits but men as a group benefit from the oppression of women as a group even so. This system of benefits is maintained by force, the threat of force and sexist ideology.

We suggest a tripartite development (of the advantages to men from the oppression of women) along the following lines would be a useful contribution to theory:

- Gains around sexuality viz. The control of reproduction (when and if not all), the control of children, the reduction of female sexuality to that of a service function

- Economic gains viz. Women’s unwaged as well as women’s waged work

- Prestige and status gains viz. Self-confidence and sense of superiority due to female labour in shoring up the male ego; the deferential behaviour of women.

Why do women refuse class-consciousness?

- It is difficult for women to accept that men hate and fear them despite overwhelming evidence

- Emotional and economic dependence of women on individual men

- Acceptance of different economic classes means that many women feel they have more in common with working class men than with other women (Margaret Thatcher)

- For many women being a ‘house nigger’ rather than a ‘field nigger’ has unrefusable advantages

- The recognition of sex class means a reassessment of relationships with men which can be agonising and frightening

- It is difficult to give up the ‘but I am the exception’ position and to begin to feel the humiliation such a position is meant to obscure. You have to accept your own self-contempt.

- The recognition of sex class does not allow easy, liberal solutions to our oppression as women.

- The more oppressed women are, the more urgent it seems to be to make alliances with the oppressors

Reproductions

- Is biology irrelevant because everything is cultural and hence transformable? Gender is certainly a cultural artefact but sex is immutable and there are two biological sexes. It is not our biology that oppresses us, it is the value that men place on it. It forms the basis for the ideology of female inferiority and the struggle of men to control children. Our biology oppresses us because of the value men place on it, per se it is not oppressive.

- But even so the female reproductive function is crucial to our analysis of the oppression of women. We see sex class as arising from biology but we do not see reproduction as a limitation on women, rather we see it as a potential strength of women. If it were not men would have no reason to expropriate it. It is not that women have inferior status from bearing children that causes our inequality, it is the superior status accorded to men in the function(s) they do alone – it can be a thing of as little apparent significance as playing musical instruments (which the women never see). But whatever it is it must be regarded as more important than anything else in that society, by the women as well as the men. It is from the sole performing of this function that their power derives. In our own society men have elevated and appropriated production and put it in opposition to reproduction. They have developed a whole political theory around the view that production is the basis of society. (Even Marx acknowledged that Marxism contains an element on ideology and this is it).

- Current thinking within the Women’s Liberation Movement would seem to represent this 9 month long experience as somehow ‘irrelevant’ to the ‘human being’ in a woman which is still seen as basically the masculine experience. Even within the WLM reproduction is devalued. In this way we fall victim to the male ideology.

Firestone argues that the male need for power will vanish if women give up their power of reproduction. However, it has to be remembered that women are not in a bargaining position where this argument might make sense. They are not on an equal footing with men. On the contrary if we give away even a fraction of the power we possess the most likely effect is that we will be crushed by the sheer momentum of male power. Already the work being done in artificial reproduction suggests this will be the case*

- Because it is in no men’s interest (including the male left) to conceive of a classless society female reproduction (as a strength of women) must be devalued. If we hate Patriarchy as it is now we must hate it as the only future men can conceive and what that will mean for women as a class in the transition towards that future.

We do not want reproduction turned into a rationalise form of commodity production. This is made clear by the Marxist tendency to treat everything as production.

In Capitalist societies when biologists talk about artificial reproduction they talk mainly about reproducing men. When they do talk about women, they envisage women of the order of Marilyn Monroe and Elizabeth Taylor.**

Changes in reproduction are crucial; they will change people and thus the nature of humanity. ‘People’ do not come from assembly lines – men will get what men can imagine.

Conclusion

Understanding that women are a class suggests certain strategies and tactics. Our strategy should be to build the class consciousness of women. Our tactics must be those that expose male power and how it operates. We suggest actions around rape and violence within the family including incest will have the most consciousness raising among women.

Rape and other sexual assaults are important because they show what it is that men hate and fear about women, i.e. their reproductive potential. Crimes of violence clearly divide men from women as they are not economic class specific. In this way the enemy is exposed.

*See ‘Women’s Liberation, Reproduction and the Technological Fix’ by Hilary Rose and Jalna Hanmer

** Contemporary science fiction written by male scientists have posited genetically engineered ‘model’ nuclear families. You can imagine their composition. And a ‘race’ of ‘human’ males served by programmed robot subservient women.

♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀♀

The Need for Revolutionary Feminism – Sheila Jeffreys

There is a need for revolutionary feminism for two very important reasons – one is the liberal takeover of the women’s liberation movement and the other is the grave lack of theory in the movement.

The Liberal Takeover of the Women’s Liberation Movement

There is a widespread hesitation to use the word ‘liberation’ and the reason given is that ‘lib’ is used pejoratively in the media and as a result the word has committed verbicide and now can only serve to provoke amusement and distaste. I believe that this tendency fits in well with other developments within the movement over the last few years towards a playing down and restricting of our revolutionary potential. There is a growing trend towards seeing the transformation of sex-roles as the desirable end of women’s liberation. Sex-roles can be transformed without any real change in power. Men can do housework and run creches but this change of roles, which even the revolutionary left sees as desirable can serve the interests of a state which seeks to have women at work without too much dissent and commotion. Will this change in sex-roles lead to women raping men and sticking kagged objects up them on waste ground? I think not, since the way male sexuality is used to control women on the streets, e.g. flashing and rape, will continue while men are the ruling class and changing sex-roles does not seriously threaten their power.

Another development is the ‘educational’ role of women’s liberation. Quite a few women’s groups have taken it upon themselves to talk to Women’s Institutes, church groups, etc. and have deliberately played down the meaning and the frightening aspects of women’s liberation, eg. by concealing or even lying about the fact that they are lesbians. The women’s liberation movement is, and should be seen to be, a threat, and I cannot see that it serves a useful purpose to represent it as a mixed Tupperware party with men doing the coffee.

Another development is towards life-stylism. It is possible to live with women, be in a women’s food co-op, attend classes at the WOmen’s Free Arts Alliance and go to women’s discos. Meanwhile the need for political feminism, the development of theory and strategy to wrest power from the hands of men is ignored. What will happen is that the women’s liberation movement will be transformed into a socially acceptable alternative to the Townwomen’s Guild under their noses, and then it will be too late.

Another problem is Spare Rib. The ethos of the Spare Rib Collective is, apparently, to eschew theory or indeed ‘radicalism’ since the paper is aimed at a wide spectrum of women and at encouraging women in to the movement. Therefore Spare Rib becomes bland and platitudinous and anger and hate towards men – on which all the energy of the movement was originally based – are completely left out.

The Need for Theory

My second reason for the need for revolutionary feminism is the lack of theory in the women’s liberation movement. There is enormous suspicion of theory as being a male invention and writing about the personal, lifestyles and sex-roles purports to be theory in itself. Meanwhile, socialist feminists produce theory which is an adaptation of Marxism, and indeed they are doing this with such prolific strength that they are seen to have fulfilled the ga which was the lack of theory and strategy for feminists. I do not accept that they have. There used to be ‘radical feminists’ who produced theory of the reasons – historical, psychoanalytical, etc – for women’s oppression and tried to suggest on the basis of their analysis what strategy women should adopt to end it. Perhaps they still exist, but they are not making themselves felt and seem to have gone into hibernation. It is exciting to read about radical feminism when entering the WLM but it is difficult to find any women who actually espouse and expound radical feminist theory.

In fact, the term ‘radical feminist’ is now used to cover such a broad spectrum of positions that I do not consider it a very useful term to describe a revolutionary feminist position. Revolutionary politics is about power. It involved the concept of power being in the hands of a particular group in society and being used to exploit and control another group or groups. It involves the determination to wrest power from the ruling group and to end their domination. It requires the identification of the ruling group, its power base, its methods of control, its interests, its historical development, its weaknesses and the best methods to destroy its power.

We need theory so that we can work out what are constructive and potentially revolutionary demands for women. We need it so that we do not just lump together the spectrum of apparently feminist demands at present being made, as equally desirable. We need to know where to put our weight so as to expose and embarrass men’s interests and weaknesses, to force them to take a stand and reveal their colours. Such an issue could well be fatherhood or total female control over childbirth.

The Basis of Revolutionary Feminist Theory

Becoming a revolutionary feminist does not require the abandonment of socialism. As a revolutionary feminist, I see in existence two class systems, on is the economic class system based on the relationship of people to production, the seconds is the sex-class system, based on the relationship of people to reproduction. As a woman, it is the second class system which oppresses me most and which dominates and pollutes my day-to-day existence, through my dear on the streets at night, the eyes, gestures and comments of males in every contact with them, etc. To be a socialist feminist, I would have to accept a unity of interests between myself and a group of men and to accept a unity of interests between myself and a group of men and to accept that my fear and humiliation come from capitalism and not men, and that I cannot do.

To construct revolutionary feminist theory, concentration on reproduction is crucial. It is in no way enough for revolutionary left groups to hold workshops on ‘sexuality’ or the ‘family’. They must talk about that frightening and difficult subject, ‘reproduction’. Economic class could be eliminated in the socialist society of the future. The son of an ICI director brought p on a Lambeth council estate would resemble anyone else brought up on that estate. Colour would be eliminated as a division by turning the world into a ‘great big melting pot’. But the differences between men and women cannot be eliminated. Women’s bodies are the factories in which children are produced and who controls these factories controls the reproduction of life and the future of the human race itself.

Patriarchy, the rule of men, has existed from as far back in human history as we have evidence for (before the economic class society). It is based not only on the exploitation of women as a class, but upon the ownership and control of their reproductive powers. No matter how much we ‘socialise; childcare and how much toilet cleaning men are constrained to do, reproduction will still be a female function. I was disturbed to hear, at a socialist feminist workshop, of the desirability of the socialisation of our bodies. For whose benefit? Men already control our bodies and could cheerfully do so in the future in the name of ‘socialisation’ of our bodies and the collective ownership of children.

The above ideas are a fraction of the debate around the idea of sex-class and are meant to promote discussion. If I have trodden on any toes, it is in the hope of provoking a response. It is my aim that a strongly political feminism can develop around revolutionary theory so that the WLM can remain a LIBERATION movement, I would also like to see a network of women develop, who are interested in discussing these ideas because it can be very lonely and frustrating to be a revolutionary feminist even within the WLM.

Male Sexuality as Social Control – Sheila Jeffreys

The penis and class struggle

What I am going to say does not obviously lend itself to a class analysis (Economic class that is). I start from the premise that there are two class systems, which exist side by side, in some areas closely interwoven and in others independently of each other. One is the economic class system, the other is the sex-class system, based upon the relationship of people to reproduction. In the sex-class system men have power over women because they control the means of reproduction which are women bodies. The products of reproduction are children and these also, males have always controlled. Men have, and so far as we can tell at this point, always have had power, economic, military, political and ideological over women. The exact forms of control can and do change according to the culture the historical period and according to changes in the development of the economic class system.

The purpose of this form of control

I would like to examine in detail a form of control which is particularly important and evident at this time. This is control through the exercise of male sexuality. So that women do not rebel it is necessary that they internalise their oppression, that there is a feeling of inferiority built into their personality structure, that their movement and personal freedom and bodily integrity are all restricted, and these things and much more, the exercise of male sexuality is designed to do.

The difference between sex and politics

Male sexuality is penile sexuality. We live in a phallic culture in which sexuality is generally defined as that which relates to the penis and the penis itself is used as a physical weapon and as a symbol in graffiti etc. Why is the penis so important? Is it important because it is the symbol of the ruling class, i.e. men. It is that which distinguishes one class from another and to males it is a badge of office. Thus in a society in which whites have power over blacks, the colour white acquires great symbolic significance/ IN an empire in which Britain ruled over colonised territories and was supremely powerful, the British flag (or passport) had such importance. Thus the act of flashing (indecent exposure of the phallus) can be seen as the equivalent of flag-waving by British cruisers in foreign waters.

By grasping the symbolic significance of the penis we can understand what is going on in the bedrooms and on the streets and on the walls of public lavatories. Much which is quite clearly pure power politics, is forgiven or explained by ‘sex’. When the adolescent youths I teach scrawl penises over any materials they are given to read, this is interpreted indulgently by the male lecturers as being a ‘natural and healthy flowering of interest in sex’. I see it as symbolising the young male’s growing realisation that he is in a superior class. He has come into his dominion and is of course fascinated by that which gives him his superior status, the penis. When these young males draw very large, erect penises on the blackboard, to greet me as I come into the classroom, they are saying that though I am a teacher, they are members of a more powerful class. They are putting me in my place, not acting out for their all-pervading interest in sex. It is not sex which is at issue but power.

Similarly, I was not upset those times in my adulthood when I was ‘flashed’, because I was too puritanical and inhibited about sex. I would complain and report flashers and my male friends would be horrified at my cruelty, fancy getting this poor inadequate bloke with a sexual problem into trouble. I was affronted and I know now that his is because the man was trying to humiliate and oppress a female by showing off to her the symbol of his power. It is a shock to be wandering, deep in thought, along a road, or sitting in a train carriage and to be suddenly confronted with an excited man thrusting his often unexcited organ into your field of vision. You are being reminded that you are a member of an oppressed group.

Towards a new definition of sex – the sensuality continuum

What is sex? In our culture sex is usually defined as being about penetration of the female by the penis. In this form sex is an aggressive activity in which the penis, symbol of authority, is wielded as a weapon, in which the physical integrity of the woman is breached and her body is invaded as in conquered territory. Lso the man is able to constantly reassert his ownership of the means of reproduction (the women’s body) and to assert his right of access to it. It follows that any activity which threatens the rule of the penis and undermines is sway, is rebellious, despite the fact that female sexual satisfaction is seldom dependant and often cannot be achieved by the wielding of this organ. So homosexuality, masturbation (even for a man, since the proper use of the penis is to subdue women) affectionate touch and all forms of non-penile sensuality are treated with suspicion or actively disapproved of or legislated against. Thus what is most commonly regarded as ‘sex’ in our culture e.g. penile sexuality is more easily understood as law enforcement or property rite or pure power politics than as a form of pleasure. If we cast aside this definition of sex, it becomes difficult to work out what ‘sex’ is. How does intense sensual pleasure and excitement shade into ‘sex’ or does ‘sex’ not exist as a seperate category. Excitement on a sunny morning the feel of velvet on the lips, the rhythmic delight of the dance, the ecstasy of neck massage, do these only change into ‘sex’ if orgasm takes place?

What is a feminist definition of sexuality? ‘Sexuality’ is a social construct. In different cultures, more or less emphasis is placed on the potential and on the nature of sexual appetite. In our culture, male ‘sexuality’ is constructed to take the form of ‘irresistible urges’, the need to put the penis into a hole to achieve satisfaction, the connection and confusion of violence and sadism with sexual activity and a quantitative approach. (How many natives have your subdued today?) All this is necessary to the use of male sexuality as social control. In whose interests are current attempts (sometimes even evident in the WLM) to construct female sexuality on a male model, around irresistible urges, orgiastic potency and quantity. A feminist definition of ‘sexuality’ might be to cease using the term and to speak instead of a sensuality continuum in which ‘penile sexuality’ and even ‘orgasm’ are seen merely as forms of sensual experience not totally seperable from the feel of a breeze on the skin.

The Guerrilla Warfare of the streets

Connected with everyday ‘penile sexuality’ of the bedroom are the terror tactics and guerilla warfare of the streets. From an early age, female children and a few male ones, are subjected to sexual molestation in the streets, parks, etc., by males. The most common form of this activity is flashing, closely followed by ‘feeling up’ and violent sexual abuse such as rape. Do women molest children sexually? We would have to fall over ourselves being liberal to suggest that they do. In an American study, 97% of the offenders were male and 9 out of 10 victims female (quoted in ‘The Radical Therapist’, Pelican books, in an article called ‘The sexual abuse of children: A Feminist point-of-view’.) The effect of the sexual molestation of children is that they grow up apologetic, frightened of moving about freely, confused about their rights in sexual situations, etc. The guerilla warfare of the streets is an effective form of control.

All this prepares women for the experience of rape in adulthood and gives them the fear of it so that their freedom is restricted. We know that rape is not about ‘irresistible urges’ but is usually planned and seems more concerned with aggression with sexual satisfaction, since penetration is often perfunctory or not possible through impotence, and ejaculation often does not occur. Race is the ultimate expression of the sex war and it is clearly about power politics and the use of the penis as a weapon.

What is to be done?

What are the implications of all this for socialism and for feminism? FIrst of all it would be interesting to work out to what extent the flowing of ‘penile imperialism’ and this particular stage of capitalism coincide and are connected. Could it be that when the more obvious forms of control such as economic and legal are being attacked and thwarted to some extent, that a more subtle form of control, harder to fight or identify, should come to the fore? Secondly, how can it be fought? It can be fought by exposure. Whenever any act is excused as being about sex we can point out that sexuality is a social construct, and examine it instead in terms of power politics. Meanwhile we can develop all forms of rebellious sensual activity which do not relate to the penis. I do not think that rape and sexual abuse of children will end as ‘sex roles’ change but only when male power is broken. Only when the penis is not a symbol of real power and status, will it cease to be used as a weapon and a form of social control.

(Paper given at the London Socialist Feminist Sexuality Workshop)

Towards a Radical Feminist Theory of Revolution – Some Suggestions on Structure

Introduction

We see a revolutionary feminist organisation as being for committed feminists, within the Women’s Liberation Movement, who want to find a political expression for their feminism in terms of theory and related action. We see patriarchy as the basic structure of oppression, and our analysis if the oppressor and the mechanism of that oppression leads to action that directly challenges male supremacy.

- What form of organisation?

The WLM is a non-centralised and non-hierarchical, as a direct response to the complex nature of the oppression that it evolved to fight. We want to attack the patterns of dominance and submission through which wine are controlled, as well as their material manifestations. Therefore we feel that the organisation should be consistent with its aims and not rely on traditional authoritarian structures. Some structure is necessary, in order to co-operate in and co-ordinate political action, but this would be as flexible and possible to prevent concentrations of power and allow a creative response to changing situations.

- Small groups

We suggest that the basic unit of this organisation should be the small group, of 6 to 10 women. The reasons for this are:-

- the need for all to participate in the process

- The need to build relations of trust as a basis for action

- The need to integrate the personal and political

- The practicalities of decision-making and taking action

- The activities of the small group

- Consciousness-raising

- To work out theory – and continuing analysis of the patriarchy leading to effective and consistent direct action

- Action and assessment including open and direct criticism both of our actions and if the personal dynamics involved

- Co-ordination

While a small group may be involved in specific local action, if we want to operate on a larger scale, we need some form of co-ordination. We need to be able to take collective decisions in a national scale, and make wide-spread spontaneous action and communication between groups possible.

Means

- for collective decisions and discussions – newsletter (forum for discussion of topics to be considered at meetings) – regional and national meetings.

- For spontaneous action – telephone tree, carrier pigeons, any suggestions?

This was written collectively by Lynn Alderson, Suva German, Sheila Jeffreys, Catherine Lunn, Janet Payne, Jan Winterlake.

SOCIALIST FEMINISTS RESPOND…

Against “Sex-class” Theories – A group of socialist feminist women, London, October 1977

Introduction: Why we wrote this.

Socialist feminism is still in the early stages of defining itself. There are many differences between is which have not been clarified or even recognised. At the same time, there is still a great deal of confusion both about the relationship of the socialist feminist network to the wider Women’s Liberaton Movement and its relationship to the organised left.

As a group of socialist feminists we are convinced that the SF network has a basis for existence as a distinct political tendency, not just within the LM but within the Marxits left. However, in order to establish our identity as a tendency it is essential to clarify and debate our differences as well as what we hold in common.

This paper is a contribution towards the debate. We decided to write in response to Sheila Jeffreys’ paper because, while we all felt strongly in disagreement with the position they take, we are also aware that there is no ready-made alternative and that is was important to begin to try and thrash one out; also the papers were being widely discussed and they draw attention to important gaps in Marxist analyses of women’s oppression. The first section of the paper deals with Sheila’s papers in the context of the WLM, its theory and politics, while the second section analyses it in relation to traditional left-wing politics.

The ‘sex-class’ debate and the women’s movement today

In her papers (The Need for Revolutionary Feminism, Male Sexuality as Social Control, and Worker Control of Reproduction, referred to hereafter as NRF, MSSC and WCR respectively) Sheila has raised certain central issues on the nature of women’s oppression which need to be thoroughly debated. Her argument in all three papers is based on a sex-class analysis in which a feminist revolution involved two seperate, equal and simultaneous struggles i) against capitalism: the relationship of the worker to production, resulting in the class system (economic) and ii) against patriarchy: male control over reproduction, resulting in the sex-class system. Because her theory does not confront the relationship between these two systems, the economic and social context which contains the ‘relationships of reproduction’ is referred to but never analysed, thus the cause of our oppression is seen as a male drive for power over women – a ‘disease’ explicable only in terms of biology, however much Sheila tries to assert the contrary.

Sheila’s theory aims to be an alternative to the ‘liberal takeover’ of the WLM, and to supercede the division between socialist women and feminists (WCR, Catcall 5, p.16). She dismisses out of hand socialist feminist theory as an ‘adaptation of Marxism’ which has failed to confront the basic question concerning women’s oppression. We do not claim to have ‘filled the gap which was the lack of theory and strategy for feminists’ (NRF p.1) but we hope that this criticism of Sheila’s approach will be a contribution towards it.

What is the appeal of the sex-class theory?

The notion of sex-class has an immediate gut appeal, especially as there is no revolutionary socialist analysis which deals with sexual oppression. WHile women have initiated various campaigns around reproduction (abortion, sexuality, child-care, contraception, etc.,) this has been done in the face of inadequate theory which has lead to largely defensive campaigns. Left groups have simply transferred their practice – developed in the sphere of production – to ‘women’s issues’, the political rationale being to radicalise women workers as part of the general (male) class struggle. The WLM has orhanised spontaneously in the attempt to create a new feminist practice, but the absence of a developed theoretical framework has resulted in a lack of persective whcih has often led to the disillusionment to which Sheila refers. There is a feeling that the aggression which characterised the WLM originally has been dispersed through reforms such as the Equal Pay and Sex Discrimination Acts, and through (non-feminist) camoaigns such as the WWCC and NAC, by a liberalisation of attitudes towards sex-roles etc; the low turn-out for events such as the picket of the Miss World Contest are interpreted as a sign in the decline of revolutionary anger amongst women in the movement.

In one of her papers Sheila reincites this anger by locating a specific area of our oppression: male sexuality as an instrument of women’s subordination, and her vivid description and forceful style increases its appeal. However, although the concepts used purport to be ‘materialist’ in its method of analysis. Her attempt to explain women’s oppression by reference to a single root cause leads her to a biologistic explanation, and we shall argue in this paper that a biologistic explanation is not a materialist one.

Sheila is describing areas of sexual oppression which up to now have been more or less ignored by Marxists. The forcefulness of her approach suggests that she is daring to confront questions also swept under the carpet by the ‘liberal takeover’ and by socialist feminists. We are arguing that her approach cannot equip us to confront our oppression adequately.

Two class systems?

Sheila argues that the Marxist analysis of society is inadequate because it ‘allows no place for a concept of patriarchy’ (WCR, Catcall 5, p.16). She seeks to rectufy this by providing us with the ‘sex-class’ system in which patriarchy, the mode of reproduction, exists alongside capitalism, the mode of production.

Patriarchal society, according to Sheila, is one in which men control the means of biological reproduction. She discusses reproduction in relation to two major spheres a) the family and b) other institutions directly concerned with biological reproduction, such as hospitals, birth control clinics, etc. Her analysis separates out the family as the basic institution of patriarchal society, because, she says, the authority and organisation of the patriarchal state is based on the patriarchal family; abolition of the patriarchal family would therefore result in the collapse of the patriarchal state since its main support would have been eradicated. But, using the same argument, a matriarchal family where women controlled their own bodies would constitute the basis of a matriarchal state. Her argument suggests that a matriarchy could exist within capitalism. This implication is also contained in her analysis of male control of other areas of biological reproduction. Male power is based on the ownership of the ‘means and forces of reproduction’ and female liberationists should base our strategy on seizing control of them ourselves. The definition of reproduction however, is limited to the physical act of producing children, and female control of reproduction is seen in terms of control of institutions concerned with this. Thus: ‘If women had control of reproduction, safe and simple abortion apparatus would be available for them to use in their own homes, self-help would be vastly increased’ (WCR p.18).

This definition of reproduction contains a number of things we cannot accept. Firstly that simply to replace all men by women in jobs concerned with biological reproduction would automatically lead to changes in the organisation of reproduction, such that women would no longer be oppressed. Sheila seems to have a notion that women are somehow more ‘human’ than men (see p.23 Catcall) and automatically know what is best for women in general. This is analogous to the argument that working class instinctively ‘knows what its interests are’ and will automatically undertake the task of transforming capitalism in a historically correct manner.

Secondly, her insistence on analysing reproduction as a system separate from the mode of production (capitalism) leads her to analyse patriarchy as a social system in its own right. This leaves her with no basis from which to analyse the relationship between the two ‘systems’, nor how the mode of production might limit changes attempted in the sphere of reproduction. The way is thus left open for reformist strategies which render female control of reproduction quite meaningless, e.g. control of the ‘means of reproduction’ as defined here would reinforce rather than challenge the sexual division of labour. Even an extension of the strategy for seizure of control to the government and all institutions is not in itself a recipe for any specific changes in the nature of these institutions. Without an analysis of the relationship between women’s role as reproducers and the other complex relationship which make up capitalism as a whole, there is no basis for carrying out the necessary changes. Sheila’s analysis, based on the separation of the spheres of production and reproduction, is quite consistent with the reformism of NOW (USA) and the ‘liberal tendency within the WLM, which Sheila is attacking.

Redefining patriarchy

Sheila defines patriarchy as society controlled by men, whose power is based on their control of reproduction. We would define patriarchy as a system of social relations, in which the dominant ideas and institutions reflect women’s inferiority. From this approach the difficulties inherent in Sheila’s approach are apparent. The oppression of women in the home is not a simple consequence of male control over reproduction, it is also integral to the capitalist mode of production. Prior to the development of capitalism the family formed the basic unit of production, although the sexual division of labour existed, women’s work was as essential as men’s to economic activity. Nonetheless there is evidence that women were considered inferior in relation to men in other spheres, such as political and religious. The relationship between women’s economic position and their social status is under debate. There is evidence to show that women’s sexual oppression predates the rise of class society. However, this is not sufficient basis for asserting that the root cause of women’s oppression is men or ‘male power’. What is at stake are different modes of analysis, one of which (Sheila’s) locates the root of oppression in collections of individuals (men), the alternative, which we are putting forward locates oppression and exploitation in sets of social relations and the dynamic by which they develop. Human agents are the supports of these social relations rather than giving rise to them.

These two approaches lead to different political strategies as will be shown below, as well as to different analyses of the material which research is still bringing to light the origins of women’s oppression.

We agree with Sheila that an understanding of patriarchy is fundamental to an understanding of women’s oppression; however, she reduces the concept to ne of biology and it refers only to a supposed male desire for power over women. She uses the concept as an ahistorical and non-specific explanation of oppression. Capitalism exhibits the ‘symptoms’ of the disease, but the disease, patriarchy, is unchanging. We would argue that under capitalism patriarchy has been transformed and given new meaning. In other words, as Sheila might agree, capitalism has given patriarchy its specific form, but the fact that patriarchy may predate capitalism should not lead us into the trap of analysing it outside of any historical context.

‘Sex-Class’ and ‘Economistic’ Marxism

In the previous sections we have made various criticisms of Sheila’s arguments and tried to indicate how her approach leaves various areas of confusion. In this section we try to show how the confusion is inherent in her approach and suggest the basis for an alternative which can more adequately take up the issues she raises.

In the sections below we discuss the inconsistencies which flow from this approach, and from Sheila’s conception of the ‘material base’. The point to be made here is that Sheila’s response to the economist approach is only one of several alternatives for Marxists. Among the debates around the adequacy of the base/superstructure model is the view that ideology itself is a material force, and cannot simply be subsumed under the economic as a perpetually secondary factor. This provides the beginnings of an alternative to the economist left and to Sheila’s positions, both of which are in their own ways reductionist. The notion of ideology as a material force can also provide a basis for the analysis of reproduction and sexual oppression which has yet to be developed, and which distinguishes us as socialist feminists from the organised revolutionary left.

Politics as power relations

Sheila’s attempt to analyse the relations of reproduction in isolation from any other social relation leaves her unable to explain the basis of women’s oppression in terms of relations at all.Her analysis of ‘relations of reproduction’ turns out to be not about relations, but about objects of ownership and control; in her writings, the concepts such as ‘means of reproduction’ refer to particular objects – women’s bodies, men’s penises, etc., and ‘forces of reproduction’ refers to the tools used in the physical process of giving birth – forceps, anaesthetic, etc. This is particularly confusing, because Sheila appears to be using these concepts in a way exactly parallel to the way Marx used the concepts of ‘forces and means of production’, which he develops to analyse the relations of production. However, in Marx’s writings, these concepts did not refer to actual machinery, factories or collections of individual workers, but rather to the social relations which characterise the way production is organised.

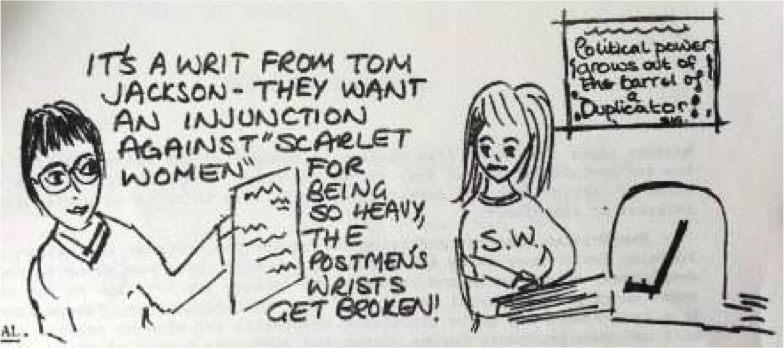

For Sheila, however, both capitalism and patriarchy are based on the ownership and control of certain objects (factories, women’s bodies, etc.) by certain groups of individuals (capitalists, men, etc.). This is illustrated by her diagram (from WCR) which shows separate models of capitalism and of patriarchy. Her model of capitalism shows the capitalists exercising their power over the working class by brute force – the barrel of a gun – in the form of the capitalist state. The prostrate worker is fed a few coins by the capitalists on the one hand, while profit is extracted from the product on the other. The model of patriarchy is similar; a prostrate woman, legs outstretched, is controlled by men via the penis, with the patriarchal family as the vehicle of control. She is fed bed and board on the one hand, while the ‘product’ – a child – is extracted for her womb (the means of reproduction) on the other. Both models locate the basis of oppression and exploitation in the ‘power’ exerted by groups of individuals, who emanate power like electricity, rather than in the nature of social relations which characterise the societies concerned. (The difference may be expressed most simply by arguing that your husband/father is not oppressive because he is a man, but rather that men are oppressive because they are husbands and fathers; that is, the problem is not their ‘essential man-ness’ hence notions of male sexual urges, etc. – but in the positions assigned to them by the social structure. The oppression of women, therefore, comes from ‘father’ and ‘husband’ and of course ‘mother’ and ‘child’.

The strategy for change, then, according to Sheila: ‘Requires the identification of the ruling group, its power base, its methods of control, its interests, its historical development, it’s weaknesses, and the best methods to destroy its power’ (NRF). The trouble with this is that it inevitably falls back on assumptions about innate qualities of the objects and people it refers to. Being innate, they are changeless, and so the analysis based on such assumptions cannot be used to analyse changes in the social formation, so as a basis for a strategy for women’s liberation it is a recipe for disaster. This can be illustrated by looking at her strategy for women’s liberation more closely.

Her papers are produced as an alternative to a certain form of economist Marxism, according to which women’s struggle against sexual oppression is subordinate to the sphere of ‘ideology’. This conception sees the class struggle as being solely concerned with issues which relate directly to the relations of production, i.e. those at the workplace; other questions are of secondary importance because while their existence arises from the relations of production, it does not directly challenge them. The struggle for revolutionary change is therefore focussed on the point of production.

Sheila does not challenge the validity of his viewpoint. While the economists get on with their analysis of the economic class struggle, she sets to work to examine the relations of reproduction as a set of separate an independent relations. This is a capitulation to the economists’ view that the sexual struggle and the class struggle are independent n some way, and it is this position which leads to the subordination of either one or the other struggles. In Sheila’s case, the sexual struggle is paramount and the traditionally conceived ‘class struggle’ is totally subordinate. Separating the two can have serious implications for political struggles. The ‘class struggle’ is seen both by the left and by some feminists as purely economic issues and raising the question of feminism is seen as a diversion, whereas we say that it is a central part of the way the struggle is conducted. Sexism is a central mechanism of the form of exploitation which women suffer – it cannot be raised as ‘just another purely feminist’ issue. The struggle against sexism will alter the form of struggle around the ‘purely economic’ issues.

The assertion that the sex struggle is a part of the class struggle without further qualification often amounts to an assertion of the predominant importance of the economic struggle and a denial of feminist analyses as being at all valid. But this stems from a narrow conception of the class struggle which we must challenge. Only a conception of it which includes the struggle against ideological and political as well as economic relations can extend the struggle for socialism beyond the narrow economic concerns.

In this section we argue that having rejected the economist approach to the women’s question, Sheila adopts many aspects of it herself which prolongs the split between Marxism and Feminism which socialist feminists are attempting to overcome. In order to fill the gap we have to reject certain aspects of both approaches.

Base and superstructure

Marxists have traditionally made a radical separation between the economic base and the ideological and political superstructure; this distinction is now being questioned. But instead of critically examining this question of the distinction, Sheila takes it over unquestionably. Whereas the economists refer continuously and monotonously to the relations of production in their analyses of all forms of oppression and exploitation, Sheila refers to ‘male control of reproduction’ as the basis of all aspects of women’s oppression. She suggests furthermore that male control of reproduction is the model or source of all oppression (WCR, Catcall, p.19). This approach has the same effect as economist Marxism, in downgrading the role of all struggles which do not relate directly to the ‘material base’, in this case the relations of re/production. For instance she says: ‘Economic class could be eliminated in the socialist society of the future… Colour could be eliminated in the ‘great big melting pot,’ but the difference between men and women cannot be eliminated’ (NRF). The implication is that only sexual struggles are ‘real’, the sexual struggle is the most revolutionary one, and as the most oppressed group, women are the revolutionary vanguard in the struggle for communism (see WCR).

By concentrating on groups of individuals, Sheila resorts alternately to the physical and the psychological in order to explain how men maintain their ‘power’ and ‘control’ over women. Penile imperialism, the ‘chief means by which men control over women’ (WCR, Catcall, p.18) is exercised through brute physical force (penetration etc.) and through women’s internalising of existing power relations so that ‘we do not even contemplate revolt’ (see also MSSC for this analysis). But the fact is that many women – Sheila included – are now contemplating revolt. If, as Sheila maintains, our oppression does stem from men, then how do we explain the fact that male control has been broken sufficiently to allow the challenge which the women’s liberation movement constitutes? And how came we begin to analyse the extent to which such a challenge might be effective under any given social system, e.g. capitalism? That is, how do we know that there are not restraints imposed on that challenge by the mode of production? We do not know, and we cannot know from within a framework which limits the explanation to a power relation between men and women. Simply to state that ‘colonised internalise their own oppression’ and to describe the mechanism by which this internalisation takes place cannot tell us anything about the origins of this oppression or its precise nature, no matter how detailed the description.

Sheila set out to show how women’s oppression is ‘at the base of and intertwined with the class struggle’ (WCR, Catcall, p.16). However the relationship exists only in the implication that men have inbuilt drive for control and ownership, combined with the assertion that women cannot be liberated under capitalism as capitalism is based on the exploitation of one group by another; there is no explanation as to why women should not explanation as to why women should not gain liberation at the expense of men under capitalism, only the assumption that we would not want to base our liberation on the exploitation of another group. The implication is that women are ‘truly human’, and that it will be up to us to humanise men through a process of reconditioning following the seizure of power of reproduction.

Conclusion

The Women’s Liberation Movement has complained very justly of the ‘economism’ of the revolutionary left, its tendency to reduce and explain all forms of struggle in terms of events at the economic level, the relations of production. But the situation on the left where politics and ideology are explained in terms of economics has its counterpart in the WLM. The left explains everything in these terms because there is no adequate theory of ideology and politics; the WLM has taken up this neglected area both in its theory and in its practice, but because of the lack of theory, has had necessarily to rely on inadequate theories of ideology and politics. This was evident in the earlier productions of radical feminism (e.g. Firestone), and is still evident in Sheila’s writings.

Again, we agree with Sheila that it is crucial to take up these questions and to formulate theory to deal with them, what we disagree with is the way in which she takes them up.

She is attempting to deal with the level of experiences of sexual oppression, why women’s experience of society is what it is, and it is important for us to explain this if we are to combat our own patterned interpretations and responses to situations and develop a truly revolutionary politics. But to explain certain aspects of our experience, we cannot rely on other aspects of our experiences; that is, we cannot explain female passivity and submission by pointing to male aggression and dominance as Sheila does. Male dominance does not explain female submission no vice versa. Both sets of responses are determined by other social relations and it is necessary to discover what they are to understand why men are ‘dominant’ and women are ‘submissive’ (which is what we experience). Sheila is using as an explanation the very thing we need to explain, i.e. male dominance as a cause of female submission. Sheila herself says that she does not know why men should have achieved power over women (WCR, Catcall, p.17), she just assumes it – as we all do every day. She has added precisely nothing to our understanding of our oppression.

The explanation of our experience cannot take place at the level of experience, we are attempting to explain why our experience takes the form that it does, and this cannot be done by reference to the level of experience; the continual reference to experience to explain experience is as a result of the non-theorisation of the ideological aspects of social relations; it is necessary to formulate new concepts to deal with this problem. It may be argued that Sheila has formed new concepts, what about ‘forces of reproduction’ and ‘relations of reproduction’ for instance? But these are not – as we argued earlier – new concepts – they are new words which behind them have the same content as the familiar biological arguments. They may sound Marxist but they are not, since they refer directly to relations between individual men and women rather than to social structures which ensure that interpersonal relations take the form that they do; Marxist concepts do not refer to interpersonal relations between biological individuals – although this is how they are often interpreted.